The following is an essay on the history of the Cornell Chapter of Acacia. Comments about accuracy and style are appreciated.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Cornell Chapter of Acacia Fraternity was founded in 1907, receiving its charter on May 30, 1907. There were twenty founding brothers, and since Acacia was a Masonic fraternity, three of the founders were professors, and all of them were over the age of twenty-one. Acacia has since changed its principles, dropping the connection to Masonry, and the Cornell Chapter has evolved into the organization it is today. In my opinion, the history of the Cornell Chapter can be divided into three discrete parts, each of which I will devote a section to in the writing of my book. The first section is the Masonic era, which lasted from the chapter’s founding in 1907 to the removal of the Masonic membership requirement in 1933. During this time Acacia lived in three locations, at 105 Dewitt Place, 708 East Seneca Street, and 614 East Buffalo Street. In 1933, the membership requirements changed so that sons of Masons and those recommended by two Masons could join. This meant that for the first time, students under the age of twenty-one years could join Acacia. And they did.

For the reason mentioned above, the second period of Cornell Acacia’s history would seem to begin in this new, post-Masonic condition in 1933. However, a second and stronger historical event suggests that the second era of Acacia’s history was beginning as well; that is, in 1934, Acacia purchased and moved into its present location on 318 Highland Road, in the Village of Cayuga Heights. The home in which Acacia, Cornell Chapter moved into was the former of Professor Henry Shaler Williams, a professor of geology and a founding member of the Sigma Xi Scientific Society. As an aside into the family who lived at 318 Highland Road, Professor Williams and his family previously resided in a cottage on East Avenue, known as the Flagg Cottage for Professor Isaac Flagg, for whom the home was built in 1881. A most commodious dwelling, Flagg Cottage was designed by the famous William Henry Miller, architect of the University Library (Uris Library), Barnes Hall, Boardman Hall (formerly located on the site of Olin Library and home to the law school), and Prudence Risley Hall, to name just the a few of his major works on campus. The Flagg Cottage was located at the present site of the northeastern meeting of Phillips and Duffield Halls at address One East Avenue. East Avenue did not end at any quadrangle in those days, but instead continued straight through to where Rhodes Hall is located, stopped at a t-intersection with what a road called South Avenue. The cottage, one of the last three to remain on the campus, was removed in the early 1950s to make way for the newly developed Engineering Quad, and specifically Phillips Hall. Of interest to Cornellians seeking to learn more about the history of the Cornell campus is the most excellent book by Kermit Carlyle Parsons, the Cornell Campus (Cornell University Press, 1968; I would add parenthetically that Parsons mentions that the Williams family occupied the Flagg Cottage from 1889 to 1891, moved to Yale for a time, then returned to live there from 1904 until the mid-1930s. I suspect Professor and Mrs. Williams called the current Acacia house their home and used the cottage as they found convenient. The cottage, though owned by the Williams family, was built on land owned by Cornell University, and Cornell reserved the right to use that land as they saw fit. There were many cottages on East Avenue, and slowly but surely, they were being displaced in favor of academic buildings. When Williams was considering building a home of his own in 1905 and 1906, he must have foreseen the day when his cottage would be destroyed for academic buildings. Also, he surely desired a home to call his own, with land of his own. Coming from a wealthy family and good salary as professor of geology, he could surely have afforded it. Henry Shaler Williams died in 1918; his wife, Harriet, died in 1932. While Parsons does not have more details as to the fate of Flagg Cottage or who might have lived there after the Williams family, I am investigating this question in further detail).

Acacia purchased its home from Clifford Williams, daughter of Henry Shaler and Harriet Williams in 1934. Clifford was seeking to sell her family home, and likely sold the Flagg Cottage at that time as well, possibly back to Cornell University, but possibly to another professor. The home at 318 Highland Road was called Northcote by Williams and his family because it sat north of Cornell University. The suffix “-cote”, like the English word “cot,” refers to a small house. Thus, Northcote was a small house north of some place. Indeed, Northcote was a small house, but still large enough to house Williams and his family, though as Carol Sisler notes in her Enterprising Families of Ithaca, her children were all grown up by 1907. Still, as Harriet willed Northcote to Clifford in 1924, Clifford never tarried far from her family. When Clifford sold the house to Acacia in 1934, she used her inheritance to build the house next door at 322 Highland Road, where she lived until 1960 (for more information on Clifford Williams, see Sisler’s Enterprising Families of Ithaca).

The Williams’ family employed the architectural firm Gibb and Waltz to build their home in the Chicago Prairie Style so well espoused by Frank Lloyd Wright. Arthur Gibb was a student of architecture at Cornell University, graduating in 1890. He built many structures in Ithaca and Cornell, including Baker Hall. With Northcote, Gibbs and co. designed a house meant to feel intimate. Low ceilings marked the second floor, including archways along the hallway. The master bedroom was on the second floor, at the center of house, and overlooked the lake with unobstructed views. Two matching closets were at the eastern end of the room, as well as a fireplace along the south center wall. A master bathroom, large enough to accommodate a tub adjoined the room and the corridor.

The master bedroom opened onto a small foyer overlooking the portico outside through five windows and over the master staircase. Down the hall to the south was the study, a room for a telephone, a bathroom, and at the end of the hall, the end room, which entered unto a balcony through a set of attractive French doors. The end room was likely a guest room. From the second floor foyer to the north were two smaller rooms to the right, likely bedrooms. To the left was the bathroom connected to the master bedroom and a sewing room.

The corridor continues into the back stairs, a wooden spiral staircase that went from basement to the third floor attic. Continuing north past the spiral staircase one entered two rooms with an adjoining bathroom. This was may have been an apartment, which could be rented by the family to boarders. Today, the “suite” has the feel of a separate apartment. Liquor and bootlegging equipment was kept in the crawl space at the northern end of the house, as Prohibition began on January 16, 1920. Interestingly, Delta Zeta sorority lived in Northcote in 1920, when Harriet rented her home to the family. Perhaps Harriet lived in the Flagg Cottage during that year, but in any case, the lease was not renewed in 1921, and as far as I can determine, no other group lived in Northcote until Acacia purchased the house in 1934.

The third floor of the house was an attic, filled with closets and eaves. The attic was and is unheated, and the dormer windows were covered by wooden vents rather than glass windows. No one in the family slept there, and the space was most definitely used for storage.

The first floor was as comfortable as the second. The main door was covered by the portico. A small porch extended from the door. A vestibule entrance allowed for the visitor to enter the front door, wipe his shoes, and then enter the house through a second door. Upon entering the house, the visitor was greeted by a phone and cloak room to their left, adjoined to the main stair case to the second floor. To the extreme left was a sliding door to enter the library. Straight ahead was a folding door to enter the living room, and to the right was a sliding door to enter the dining room. The living room featured a fireplace, beautiful bay windows overlooking the lake and a growing oak tree, and wood paneling. Another French door stood against the eastern wall for easy access to the sprawling back lawn, but this door could be covered by curtains and concealed if so desired. A piano was in the corner to the right, providing merriment to the guests.

The dining room was could also be made an enclosed space, as three doors against the northern wall and the sliding door into the foyer and a folding door into the living room provided closure. On the eastern side were windows overlooking the lake and to the west were small square windows inset in the upper part of the wall, providing a banquet like atmosphere. Each room was originally called a chamber on the house blueprints, and these windows, when combined with the candle lantern style electric lights, added to the feeling of a dining chamber.

Returning to the library, the third and final fireplace graced the northwestern corner of the library. The sliding door was not the only entrance to the library, as a second sliding door, this made of wood and with no windows, entered back into the living room. The library itself featured hardwood floors, large windows to the east and west, and a set of double doors to the south. These double doors entered a porch underneath the end room. The entrance to the library was likely the one Henry Shaler Williams preferred, as he could be immediately warmed from the cold Ithaca winter by the fire in his library. The double doors, one for going and one for coming, also suggest the room was in good use.

The library was lined with wooden shelves and charming, small rectangular lights covered by opaque shades. These lights did not cast much light, and instead gave the feeling of a lit candle. As Northcote was built in the age of electricity, running water, and steam radiators, these touches reminded the residents of simpler and quieter days gone by.

What kind of books were in Henry Shaler Williams’s library? Likely many related to geology, his chosen profession. Small pull-out drawers at the bottom of the shelves likely provided a space for important papers, possibly even the house’s blue prints. Overhead lighting completed the cozy, book-laden library.

Returning to the dining room. There were three exits from the dining room on the northern wall. The one to extreme east adjoined the windows and entered into a small pantry or scullery. This room had one window looking east and a second door that led to the kitchen. The next door, from east to west, was an entrance into the corridor in which the wooden back staircase proceeds to the basement and to the second and third floors. The final door, adjoining the small square windows on the western wall, led into the same corridor where the spiral staircase was located, but on the opposite side of door number two.

Once in the corridor with the spiral staircase, a door leading to a long, narrow bedroom facing the west came up quickly. This was the room for the butler of the house, a kindly man named Walter, who, according to one account, hung four coats on pegs in the service hall: one to wear when he served as butler; one when he was the gardener; one for his job as chauffeur; and one to wear when he shoveled snow.

Another door from the spiral staircase corridor led into the kitchen. The kitchen was small, but adequate. A door on the eastern wall connected to the aforementioned scullery and another door on the western wall led to a small bathroom for the cook and the butler. The kitchen of 1907 was not as advanced as ours today. With the electric refrigerator two decades away, an ice box was surely used to keep perishable foods from spoiling. A large range stove, operated by gas, was located against the far wall of the kitchen, with the various pots and pans scattered throughout.

Leading from the kitchen was a service hallway. There was a small storage room to the east and a broom closet to the west. At the end of the hallway was the service entrance itself, leading into a vestibule area outside. This was where garbage was kept and food delivered. The service entrance led to a small driveway, large enough to hold a delivery truck. The service entrance was covered by a wooden portico, with a square pattern on either side of the wall to let in light and air. A gate likely closed this covered space to prevent intruding animals at night.

This part of Northcote was very much a servants’ quarters. Although the Williams thought their house at the crest of Highland Road to be a small home, Northcote, like any home for the wealthy in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, was designed for a full-time servant to be on the premises. The butler, Walter, likely lived with the Williams family, though he may have stayed in the third floor, reserving the small room adjoining the kitchen for the cook. In later years, this room would be used as living space for the fraternity.

The remaining two floors of the house, the basement and the third floor, were unremarkable spaces in their original forms. The basement was an unfinished cellar, with access only available through the back spiral staircase. A space on the eastern wall was devoted to the storage of kitchen equipment. Another room on the southeastern wall housed the gas boiler and hot water heater. With small windows at the top of the walls, the basement of Northcote was not a very pleasant place at all.

The third floor was little better. Unbearably hot in the summer and completely un-insinuated for the Ithaca winter, the attic at the southern end of the house was little more than storage space. With wooden eaves instead of windows in the two sole windows on the east and west, the attic also had small crawl space closets for storage.

Separate from the attic were two small rooms, which may have been used as an apartment or for the house butler. The room adjoining the attic was probably a bathroom, holding a bathtub and a toilet. This bathroom had one dormer-style window for light and ventilation. The bedroom at the northern end of the third floor had two dormer windows and one slider window. This was most certainly used as a bedroom, as the three open windows would provide ample ventilation in times of hot weather. A remarkable space for its incorporation of windows into the roof superstructure, this bedroom was a cozy nook on the third floor of Northcote.

Northcote was well-equipped to house the Professor Williams and his family in 1907, and they stayed there until Acacia Fraternity bought the house in 1934. The Cornell Chapter renovated the house numerous times in the following twenty-five years after its purchase, adding bedroom space on the third floor and bathrooms on the second floor. The basement was transformed into a recreation room with ping-pong and pool tables. Another room in the basement was used for watching television.

The major change in how Northcote was utilized was in the usage of the attic space. What was little more than a storage attic during the Williams family’s day became an attractive dormitory with Acacia’s occupation of Northcote. By painting walls, laying carpet, adding electrical outlets along the base of knee wall, and closing the eaves with glass windows, the third floor dorm was the main sleeping area for the entire house. With single beds and little more lining the floor, the dormitory could hold twenty-four occupants.

While the fraternity brothers slept in the dorm, they used the rooms on the other three floors as living space. Here were stored there clothes in the built-in closets or drawers; here were their desks for homework. As the rooms of Northcote were not all designed for bedrooms, the dorm sleeping arrangement allowed for the non-bedrooms to function comfortably as living space for three or more men. The second floor bay room could snugly fit three men and their belongings with a little ingenuity of dresser arrangement. The master bedroom could hold four men’s desk and clothes.

While the attic was transformed into a dorm, Northcote was changed in other ways. With the advent and proliferation of the automobile, the circular driveway in the front of the house was fuller than ever before. The front and side entrances were the primary ones, with the entrance to the library out of fashion. By 1954, the parking lot was removed from the front of the house and placed in the back of the property. At this time, a service road was installed for apartments to the east of the house, and the fraternity, the original owners of the land on which the road was built, retained right of way on the road.

By 1961, the view of the lake was obscured by apartment buildings, the view to the west was blocked by apartment buildings and the Congregational Church, and the dazzling open feeling of Northcote’s incipient landscaping was maturing into a fine, mature adulthood. Large trees now grew along the front and back lawns, though the great bulk of the back lawn was kept open through careful mowing for open space for football, golf, and later, frisbee.

It was at this time that the owners of Northcote, Acacia Fraternity, Incorporated, made a decision that would change the face of the house at 318 Highland Road forever. With this change began the third and current era of the fraternity's housing history, that of the Wing.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Keep reading the Blog, and look out for the continuation of this essay on the third section of the fraternity's housing history.

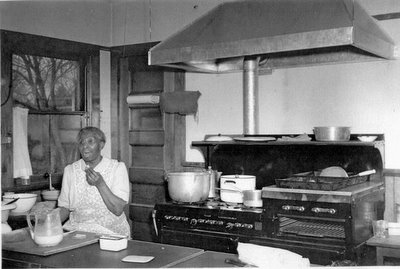

I have been wanting to post this picture of Ma Sutton since the moment I saw it.

I have been wanting to post this picture of Ma Sutton since the moment I saw it.